- Home

- Michael Morton

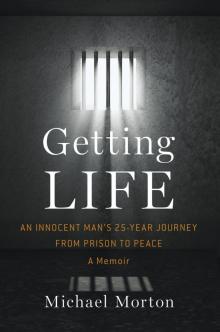

Getting Life

Getting Life Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

* * *

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Cynthia—

You have turned my mourning into dancing.

Foreword

In the movie Crimes and Misdemeanors, a brilliant and dark cautionary tale about a prominent, admired doctor who commits a murder and gets away with it, there is a character named Dr. Louis Levy, a professor of philosophy plainly based on Primo Levi, an Italian chemist, writer, and Auschwitz survivor who committed suicide in 1987. Dr. Levy was played by Dr. Martin Bergmann, a psychoanalyst who coauthored the lines he delivers as the Levy character in a series of interviews throughout the film. Levy/Bergmann gives a memorable and wise peroration just before the final credits, a statement that came to my mind the day Michael Morton was released from prison in Williamson County after enduring twenty-five years of hard time in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice:

We are all faced throughout our lives with agonizing decisions, moral choices. Some are on a grand scale. Most of these choices are on lesser points. But we define ourselves by the choices we have made. We are in fact the sum total of our choices. Events unfold so unpredictably, so unfairly, human happiness does not seem to have been included in the design of creation. It is only we, with our capacity to love, that give meaning to the indifferent universe. And yet most human beings seem to have the ability to keep trying. And even to find joy from simple things, like their family, their work, and from the hope that future generations might understand more.

Michael Morton was wrongly convicted of murdering his wife, a woman he dearly loved, and eventually lost all connection to his three-and-a-half-year-old son, Eric, the center of his world. He was shunned by most of his community, who came to believe he had committed a horrible crime. His in-laws turned against him. Despite the work of great lawyers who did everything possible, he was convicted in a trial that was both maddening and humiliating. It’s an ultimate nightmare, beyond human imagination. How does one survive, much less prevail, after such an experience? How can one find the capacity to love and find joy again in simple things? Read this wonderful book, take this journey with Michael Morton, a gifted writer with a marvelous power of observation and clarity of thinking, and you will learn some surprising answers.

Starting in 1989, as the first post-conviction DNA exonerations triggered an “innocence movement” and the liberation—no other word adequately describes it—of literally hundreds of wrongly convicted men and women, a treasure trove of remarkable books by and about “exonerees” have been written. Michael Morton has produced a memoir of his twenty-five-year ordeal that, by any fair calculation, may well be the best to date—no disrespect to John Grisham intended! Michael Morton is the innocence movement’s best approximation of Everyman—a self-described average, middle-class guy, living in a Texas suburb with a wife he adored and a three-and-a-half-year-old son, who gets up early to go to work. When he arrives home later that day, he learns his wife has been bludgeoned to death. He has no record, no experience at all with the criminal justice system. No reason to believe he could be suspected or, even worse, convicted of this terrible crime. It’s like being struck by lightning without even knowing there was a storm on the horizon. Unthinkable. Yet from Michael’s story alone, especially the way he tells it, any sane American will have to conclude that if it could happen to Michael Morton, Everyman, it could happen to me, it could happen to anyone.

I am certain this book will have far-reaching impact. Why? I can think of at least six reasons.

First Reason: The story itself is just so astonishing, especially the way Michael came to be exonerated, that it should induce a skeptical existentialist to literally get religion, a point Michael gently makes to me (the existentialist) on occasion. You will pinch yourself at some of the stranger-than-fiction dramatic turns in this story.

Second Reason: Michael is a courageous man, a person with true integrity and an unerring conscience. These qualities palpably drip off the page from his clean, fair, and generous narrative voice, which is never mawkish or sentimental. Permit me a personal note: On the eve of his exoneration, I presented Michael with an agonizing moral choice—you can get out of prison tomorrow, but if you are willing to fight some more, if you are willing to risk staying in prison for another six months or longer (I could not make guarantees), we have a chance to get the truth about how you were framed for a murder you did not commit, a chance to strike a significant blow against prosecutorial misconduct in a way that will generate some deterrence, a chance to get some legislative reforms. Michael said, “Let’s play hardball.” And our team did, with much greater success than we ever anticipated and without his having to remain a minute more in prison. Utilizing a unique Texas procedure, the Court of Inquiry, we were able to get Ken Anderson, the prosecutor in Michael’s case who hid exculpatory evidence, convicted of criminal contempt. We hope that this lesson—the value of having direct court orders that prosecutors look through files and disclose exculpatory evidence—like other lessons learned in the Morton case, can effectively and fairly deter those prosecutors who deliberately and knowingly engage in misconduct. In this book Michael is far too modest about the courage he displayed when faced with this agonizing choice, so I feel compelled to give him up in this foreword!

Third Reason: Michael is a wonderful writer, with a dry wit that never deserts him, even at his darkest moments.

Fourth Reason: This story has already proved to be compelling in other media: Pam Colloff wrote a terrific, award-winning account of certain aspects of the case in Texas Monthly. 60 Minutes did a striking segment they wound up airing three times. An excellent documentary, An Unreal Dream, produced by Al Reinert, Marcy Garriott, and John Dean, has been well received at film festivals and was aired in its entirety by CNN in prime time. But if you have read or seen any or all of these accounts, don’t worry, you will find this book even more interesting.

Fifth Reason: Michael is a remarkably effective advocate. He has demonstrated an appeal to Republicans and Democrats, conservatives and liberals, prosecutors and police. In a state with Republican supermajorities in both the House and Senate, and with the conservative Rick Perry as governor, Michael’s advocacy and example led to the passage of “Michael Morton” bills in 2013. One bill greatly expanded discovery in criminal cases. The other extends to four years the statute of limitations in attorney discipline grievances cases where prosecutors engaged in misconduct and innocent defendants were wrongly convicted, and that four years starts from the time of the defendant’s exoneration. Based on this new statute of limitations, Anthony Graves, an African American who was wrongly convicted of murder and sentenced to death in Tyler, Texas, has filed a grievance against a prosecutor who hid exculpatory evidence when Graves was tried.

Sixth Reason: Michael is white. It would be hypocritical not to acknowledge this intractable reality of American life, even in the age of Obama: the media and the general public have always been somewhat more responsive and attentive to the narratives of white exonerees. This takes nothing away from Michael’s unique achievements. His story illustrates the painful reality that a wrongful conviction can happen to anyone, regardless of race or economic background. Yet it’s important to acknowledge that race effects pervade our criminal justice system, with people of color making up more than two-thirds of the 312 wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA evidence.

Finally, no prefatory words about Getting L

ife would be complete without contemplating how close Michael came to losing his own. No one knows this better than Michael. The first sentence he uttered the day he was released from prison was “Thank God this wasn’t a capital case.” Attitudes about the risk of executing the innocent are quickly and appropriately changing. Pew Research reports that support for the death penalty among Americans has dropped from 78 percent in 1996 to 55 percent today. Without question, much of this movement is attributable to cases like Michael’s. Reasonable people can differ about whether capital punishment is a morally appropriate sanction for the most heinous of crimes, but reasonable people cannot differ about whether it is morally appropriate to execute someone who is innocent. Professor Franklin Zimring, in his masterful book The Contradictions of American Capital Punishment, has shown that attitudes in European countries, where capital punishment was repealed decades ago, are not dissimilar to those in the United States except that in Europe people do not trust the state to get it right. Remember, Michael had very good lawyers who performed well, but when a prosecutor, or any law enforcement official, chooses to hide exculpatory evidence, when winning becomes more important than playing by the rules, no system of regulation can effectively eliminate the risk of executing an innocent. This is not a hypothetical problem.

Michael speaks truth to power with moral authority that cannot be questioned, with Christian forgiveness that comes from his core. He has, indeed, defined himself by the sum total of moral choices he has made, choices that inspire and that command respect. This is a book you should read.

Barry C. Scheck

Co-Founder and Co-Director, The Innocence Project

February 14, 2014

Prologue

The door closed.

Not with a click or the sound of tumblers finally hitting their marks or the sturdy clunk of wood and metal meshing as if they were made for each other.

This was different.

It began with the long, hard sound of steel sliding against steel.

Like a train, the heavy door built speed as it barreled along its worn track, the portal to the real world growing smaller as the barrier of thick and battered bars roared into place.

It locked with a cold, bone-shaking boom that rattled me—literally—me, the guard outside my door, and any other inmates unlucky enough to be nearby.

I was alone in my cell, alone in the world, as alone as I had ever been in my life.

And I would stay there—alone—listening to that door close, over and over and over again, for the next twenty-five years.

Twenty-five years.

My wife, Chris, had been savagely beaten to death several months earlier. Before I had time to begin mourning, I was fighting for my own life against a legal system that seemed hell-bent on making me pay for the murder of the woman I would gladly have died for.

I was innocent.

Naïvely, I believed the error would soon be set right.

I could not have been more wrong.

As the years went by, I saw the three-year-old son my wife and I had doted on grow up and grow away. He believed his father was the murderer who’d killed the person he loved most.

And why wouldn’t he? That’s what everyone told him. On each of the rare occasions Eric saw me, my imprisonment—my inmate uniform, the guards and the guns, the bars and the buzzers—was a stark reminder that the world had decided I wasn’t fit to walk free.

Ironically, Eric was one of the two people who knew what had really happened. He was in the house when something evil entered and destroyed our lives. At the time, our son tried to tell others what he had seen, but no one believed him.

And through all my time in prison, through all of my son’s heartache, through our whole family’s grief, the man who killed my wife was free—free to travel, free to commit crimes, free to kill again.

And again.

As the years passed, I watched the world go on without me through the keyhole of a door I could not unlock.

For a quarter century—a generation—my life was lived in penitentiary television rooms where you could get killed for changing the channel and on hard labor farms where violent men would feign fainting just to get a brief break from the unrelenting Texas sun.

I ate every meal in chaotic and cavernous prison chow halls where, as the old joke goes, the food was terrible, but at least you got a lot of it.

Needless to say, my dining companions were much the same—they were terrible and there were a lot of them.

If I was very lucky, weekends were spent in packed visiting rooms that were either too hot or too cold, and were always overrun by shattered families—virtually all of them walking wounded, scarred by addiction, abuse, and ignorance.

While I was desperate for company from the outside, whenever I entered the visiting room, I knew there was a terrible downside for me, as well as for the people who had made the long trek to see me.

Everyone who visited had to try to act “normal” in an almost unimaginably strained setting. Because they loved me, they would ask that we pose for pictures together in front of the dirty, cracked walls washed in harsh fluorescent light. I would stand next to my family in their colorful street clothes, while I grinned grimly for the camera—year after year—getting ever grayer, looking more worn out, always in my poorly fitting prison whites.

Smile!

Click.

And on those visits, I would see my mom and dad—my biggest boosters, my eternal believers—spend year after year in shabby rooms surrounded by failure and sadness, aging before my eyes, struggling to smile through their pain, their shame, and their profound anger.

I was doing the same.

We spent all those visits and all those years talking about old times and planning for a future we could only pray would come to pass.

What none of us knew was that in the small town where I had stood trial, in a nondescript concrete warehouse where police stored old evidence—a dingy place packed with damaged cardboard boxes and haphazardly marked plastic pouches—was hidden the tiny piece of truth that would one day set me free.

Decades after I entered prison, a DNA test would change everything—not just for me and for my son but for the man who so unfairly prosecuted me. The DNA test would make huge changes, as well, in the broken legal system that tried to keep me behind bars.

For the cruel monster of a man who killed my wife, the truth came roaring out of the past with a vengeance.

This is the story of how I got a life sentence and survived what felt like a lifetime behind bars—only to have everything change again. I got my life back, and this time, I understood it.

Twenty-five years after I was swept away, the tide turned.

The wind changed.

The door opened.

PART I

PAIN

What has happened to the truth?

—JOURNAL OF MICHAEL MORTON, NOVEMBER 5, 1986

CHAPTER ONE

By the time my family moved to Texas from Southern California, I was a fifteen-year-old wiseacre crushed to be leaving the big city for the sticks. I felt like we were moving from the center of the universe to Pluto. I mourned for miles in the backseat of our old car, as my family left behind the Pacific Ocean for a sea of East Texas pines, the California mountains for rolling hills and hotter-than-hell summers.

But I had to admit that even California had nothing quite like the Texas sky.

It can still take my breath away—big and blue, wide open and welcoming. Then, in what seems like an instant, it can turn into a wind-whipped canvas for bruised and brooding clouds, the horizon streaked with lightning, a ground-shaking Old Testament storm on the way. Then it will change yet again—bathing those of us below in sunshine and forgiveness and peace—until the next time.

Since my coming to Texas as a teenager, that beautiful, terrible sky has been the backdrop

for each burden and every blessing that has come my way.

The high school in tiny Kilgore, Texas, was a fraction of the size of the school I had attended in California. I entered as a junior, accustomed to thousands of students, packed hallways, and the ever-present possibility of gangs. Instead, what I found at Kilgore High School looked and felt like an episode of the old TV show Happy Days. The classes were small, the teachers were old school, the kids clean cut and smiling. They seemed younger than the worldly West Coast teenagers I had left behind.

And because I had just come from “exotic” California, I was lucky enough to hold a tiny dollop of mysterious cool for some of them. I wasn’t exactly the Fonz, probably more like Richie Cunningham, but I had a background that boasted palm trees—something as rare as movie stars in Kilgore, Texas.

I got an after-school job as soon as I could, because I was desperate to have a car. The distances were tremendous compared to what I’d lived with in suburban California, and I wanted the freedom and self-determination that would come from sitting behind a steering wheel. So I started slinging patties at the town’s spanking new Whataburger, saving money, making friends, and looking high and low for a car I could afford.

I ended up paying five hundred dollars for a powder-blue Cadillac Coupe de Ville that belonged to Mom’s hairdresser, a flamboyant gay man named Ricky, who had inexplicably, but rather successfully, chosen conservative Kilgore as home base for his beauty shop. All I wanted to know was whether he had taken care of his car, and he certainly had.

It was a magnificent beast—with power windows, a plush interior, and an mpg of about three. The car was so massive that the first time I got it spruced up for a date, I used an entire can of Turtle Wax.

I loved it.

It’s hard to be dapper when you are a small-town kid in a too-big car, but God knows I tried. My mother had raised me to be a good date, and I prided myself on taking girls out for dinner or to a movie rather than just racing through our barren downtown on the way to split a Cherry Coke at Dairy Queen.

Getting Life

Getting Life