- Home

- Michael Morton

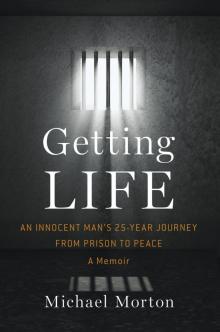

Getting Life Page 4

Getting Life Read online

Page 4

I rubbed my knee against the cushioned frame of our bed. My fingers traced the edge of the lampshade on my side of our bed. I turned on the water in the master bathroom sink, trying to wash away the fingerprint dust. It was our house and our stuff.

But it didn’t feel like ours anymore.

Our home looked like it had been picked up by a giant and shaken hard—then angrily thrown aside. Everything was in disarray. Our entire closet full of clothes was tangled and tossed on the floor. I wasn’t sure who to blame. Had the murderer or the police made this mess? The police officers who smoked had left overflowing ashtrays all over the house. They’d made no effort to clean up after themselves, acting as if my son and I were not still living there.

Everywhere I turned, there was another sign of the dark shadow that had fallen over our lives.

I desperately wanted to talk with Chris about it, but her body now lay in the morgue and her blood and brain tissue covered the walls and ceiling of our bedroom.

I looked through the window and saw the wide yellow crime scene tape encircling our home. That was one thing I decided I could handle myself. I stepped out into our dark, quiet neighborhood and walked to the side of the house where the yellow tape had been tied. As quietly as I could, I moved along the tape, wadding it into a ball—removing the most obvious evidence of what had happened behind the walls of our home.

I went back to Eric and curled up with him. I stayed there for ten minutes, then got up, walked through the brightly lit house, and went back to Eric and lay down—and then I did it all over again.

Again and again.

All night long, I glided like a ghost through our glowing house, looking for someone who wasn’t there, looking for meaning in what had happened—searching for anything to help me wrap my head around the bomb that had gone off in our lives.

As morning broke, I was still moving through the house, aching with grief and lack of sleep. I knew I had to pull myself together for Eric’s sake. I brewed some coffee, sat down, and began making the kinds of phone calls I never dreamed I would have to make—notifying far-flung friends and family about what had happened. I hadn’t even thought about making initial inquiries about funeral arrangements, or trying to figure out where Chris would be buried. It is one of the ironies of losing someone to sudden death that those hurt the most have to begin immediately making big decisions at a time when they are least able to.

I felt like a zombie, and I would for weeks. It seemed everyone had questions for me and I had very few answers. What were Eric and I going to do now? No idea. Would we sell the house? I didn’t know. Did I have any idea who had done this to Chris? None. Were the police making progress? Who knew?

The day after Chris died, my family came in full force, and I was so grateful. Eric loved them all, and they were great distractions for him when he badly needed something other than darkness and despair around him. My mom and dad were hugely helpful in squiring Eric around, playing with him for hours, and keeping both of us fed, dressed, and moving forward.

Chris’s brother John and his wife came. They were actually beginning their move from Houston to Oregon, but they stayed through the funeral. John was the oldest child in their family. He had a bachelor’s degree in marine biology and an overwhelming love for his little sister Chris. Mary Lee, the youngest of Chris’s siblings, had lived with us for a while. Chris was an almost maternal pillar for her, someone who looked out for her, guiding her choices and giving advice.

When they got there, John and Mary Lee wanted to go to the room, wanted to see for themselves what had happened. And as hard as it was for all of us, the three of us stood stricken beside the bed, trying to do our own amateur forensic work. Where had the man stood? What had he been looking for in our drawers and closets? What had he taken?

I had already told police that I knew a pistol was gone—a .45 that I kept in a leather pouch on the top shelf of our closet.

John, in particular, was angry and frustrated. He believed the police were not doing enough to look for the killer. They hadn’t been out to the house at all during the time John was there, and he was convinced they were blowing the investigation. Of course, his fears turned out to be well founded.

While I attended to the myriad demands triggered by what had happened, John told his wife he was going to take on an exercise aimed at “getting inside the killer’s head.” He stood in the bedroom and began to act out what he believed would have been the logical approach the killer used to get into and out of the room. And then he retraced the most likely path the killer would have traveled to make his getaway.

John wanted to check for any small piece of evidence that police might have overlooked.

With his wife at his side, John walked through the house to the dining room, then through the unlocked sliding glass door where we assumed the killer had entered. He walked into the backyard and toward the fence, reasoning that the killer could have parked near the wooded area behind our home, jumped the fence, and gotten access to the house.

Immediately, John found something police hadn’t noticed—two large footprints just inside the fence. They were deep, as though the person who made them had climbed the back of the fence, swung his leg over, and jumped into our yard, landing hard and sinking into the soft ground. This was encouraging for John, so he continued his trek of the imagination, this time walking out the side gate of our yard and moving toward the place he believed the killer’s car may have been parked.

One of the features Chris and I liked about the house was the greenbelt that ran behind it, a scrubby, wooded area that had not yet been developed. The secluded clump of trees and native Texas grasses was crisscrossed with small trails, superhighways for jackrabbits, deer, coyotes, and the occasional unlucky house cat. There was also an abandoned campsite, with torn-up clothes, a small blackened fire pit, and empty beer cans, a sign that two-legged varmints were regular visitors there as well. Most of the neighborhood attributed the campfires to teenagers or the occasional hobo, certainly not to anyone seen as a threat.

John was looking for something specific, however. Maybe something from our house that the killer had taken and dropped, maybe the weapon he had used to kill Chris, maybe something that looked completely innocent but held the answers all of us so desperately wanted.

That is exactly what he found.

Beside the wooded area, there was one house under construction, but work on it had been sporadic. The shell was built, but the inside remained rough and unfinished. Not far from this house, John spotted a square of dusty blue cloth clinging to the curb. It was a Western-style bandanna. John crouched down beside it, and without touching the fabric, he looked carefully at each section of the cloth. His attention was drawn to a cluster of small, dark brownish stains. He wasn’t a trained investigator, but he believed they might be bloodstains.

And he was right.

So, unlike the inexperienced officers he was making up for, John took great care to keep the evidence uncontaminated. He picked the bandanna up by its corner with two fingers and held it out from his body as he headed back to the house. As he walked into the breakfast nook, John told everyone to stay back and called for his wife to get a plastic bag that he could put the bandanna in. She grabbed a clear baggie out of a kitchen drawer, and he carefully lowered the bandanna inside.

No one had touched it any further, no one had held it, no one knew it existed.

On the same foray into the woods, John had gone into the house under construction and collected what appeared to be a napkin with dark stains. This piece of overlooked evidence, too, was preserved and packaged. John then called police, told him of the discoveries, and asked that a deputy come to our house and pick up these items.

It wasn’t long before an officer showed up, picked up the baggies, and disappeared again into the Williamson County Sheriff’s Office. It would be twenty-five years before any of us knew the true succe

ss of John’s search.

CHAPTER FIVE

Sheriff Jim Boutwell and his investigators were in regular contact with me for days after Chris’s death. The sheriff had also been speaking with local reporters, and I opened the paper one morning to see a story on Chris’s autopsy results, in which Boutwell was quoted. The article noted that the Travis County Medical Examiner Roberto Bayardo had pinpointed her time of death as 6:00 A.M.

That made sense to me. I knew that I had left at 5:30 on the dot. I also believed, naively as it turned out, that the official time of death would serve as a tool for detectives in eliminating me as a suspect. But I wasn’t thinking clearly, I wasn’t protecting myself—I hadn’t even contacted a lawyer. Why would I? It was simply beyond my comprehension that I would be considered a suspect.

Looking back, I recognize how much I was reeling from loss.

I had been a religious person when I was young but had grown away from the church in high school. It had been a long time since I thought about the significance or power of the human soul.

The vacuum Chris’s murder left in my life, though, brought some of those old teachings back. Her absence seemed to leave a gaping wound in the world, a shrieking emptiness that I had never known could exist. I believed I could feel the loss of her soul in my life.

I realized then that being married is very much like becoming one person. Chris had been part of me—a vital organ, a limb, a function I needed to live. With her gone, I felt like I was dying.

I experienced the kind of phantom pain amputees often report. When I sat on the couch, I could almost feel her beside me. When I walked into the kitchen, I could practically see her laughing and making dinner. I thought I could hear her in other rooms or catch a glimpse of her walking out the front door or tending her flowers in the yard. Her absence was so powerful, it was like an undeniable, tangible force. I spent time in my head talking to her, looking for her, trying to communicate with her, telling her I loved her, begging her to come back.

I hadn’t slept in what felt like days.

And every waking moment was filled with dark demands—from arranging Chris’s funeral, even deciding what she was going to wear, to dealing with the appreciated but seemingly unending condolences from all quarters.

First and foremost, I was trying to take care of our heartbroken little boy. I was keenly aware that Eric might have seen something terrible, that he must have felt threatened, that he may even have been assaulted in some way. Spending time with both sets of extended families was good for him to a point, but we were all struggling mightily with our own crippling anguish.

Sometimes—inevitably—it got the better of us.

I remember sitting at the table one night after dinner as my mother steadfastly gathered up the dirty dishes for us, doing anything she could to try to keep our lives as normal as possible. She’d made us a nice meal, even though no one really had much of an appetite. When I glanced up appreciatively, I saw that her face was beginning to crumple, even as she struggled to continue her task. Then she gave in to her grief, falling against the kitchen wall for support, her body racked by hard, painful sobs. A few moments later, she regained control, wiped her eyes, stood, and went back to clearing the table.

It had to be a bewildering atmosphere for a little boy, first being in the house when his mother was murdered, and then being reassured and comforted by adults who every now and then completely lost it. I started looking in earnest for a therapist who might know how to work with Eric, maybe help him find some measure of peace.

Meanwhile, I felt under siege from all sides.

The media had been contacting me day and night, pestering me to sit down for an interview that I didn’t want to do. This was not just another news event for me. I didn’t care whether it was on TV or on the front page of the paper. I didn’t care that the public “wanted to hear from me” about the terrible thing that had happened to my wife and our life together.

What I needed most were some answers.

Who had done this? Why? I believed the police were the people who would eventually deliver those answers, and I was determined to do anything I could to help them.

The phone rang and when I picked it up, I heard Sheriff Boutwell’s now-familiar voice. He said he wanted me to come down to his office and chat, that he wanted to update me on the investigation.

I see now that I could not have been more helpless, more alone, or more vulnerable.

I told the sheriff that I was on my way.

He was waiting for me, as usual, behind his massive old wooden desk—surrounded by enough Western memorabilia to open a museum. There were horseshoes on the wall, gun belts and handcuffs on pegs, and a wide-brimmed Stetson, his ever-present signature hat, atop the sheriff’s head.

The old wood-frame building was filled with the sound of Boutwell’s boys at work—the deputies’ boots clomping across the bare wood floors, the creaking complaints of heavy doors being opened and closed, phones being picked up and hung up and occasionally slammed down, and the constant low drone of their conversations, sometimes punctuated with laughter or annoyance or anger. Every sound in the place seemed magnified by the office’s tall ceilings and ancient walls and windows.

I sat down in the old-fashioned oak office chair across from the sheriff with high hopes. It soon became clear that he was not going to be the one sharing information.

I was.

Once again, he led me painstakingly through every detail of the last twenty-four hours of Chris’s life, questioning every one of my movements and choices, my habits and whereabouts. I had grown accustomed to this. A friend who had some police experience told me that this was standard practice, the theory being that if the sheriff and his sidekick Sergeant Wood could catch me in even one small inconsistency, then I would most likely crumble under the weight of their discovery and confess everything.

At least, that was the way it was supposed to work.

It was a theory that rested, of course, on the premise that I had, in fact, murdered my wife. Since I had not, going over the details again and again got us nowhere. I had no insight to offer, no clues that the police could follow up, no information that would crack the case for them.

But they kept digging.

At one point, the sheriff targeted the last meal Chris and I had together, our celebratory dinner at City Grill in Austin. He fixated on what side dish Chris had chosen to go with her fish entrée. Whenever I told him she had ordered the zucchini, he challenged me, accusing me of being wrong or actually lying about what she ate.

I was dumbfounded at why he was so obsessed with disputing this easily confirmed information. Why didn’t they just contact the restaurant and check the bill? I wondered if this was some sort of new police ploy, an attempt to rattle me and perhaps force some kind of breakthrough in the case. When the sheriff asked me again and I gave him the same answer, he made no effort to hide his disappointment and anger.

We were at an impasse. We all just sat there, staring at each other. Sergeant Wood broke his gaze and leaned over to the sheriff, pointing at a piece of paper on the desk, apparently the autopsy report. Wood whispered, loud enough for anyone in the room to hear, “I think that where it says ‘vegetable matter,’ that means zucchini. Zucchini is a vegetable.”

The sheriff looked momentarily crestfallen, then quickly went back to shooting daggers at me. Again he launched into a fresh challenge of everything I had detailed about my day.

That was the moment when I realized with a sad and profound certainty that these men were simply not up to the task of solving this case. They may have been able to handle day-to-day, hometown police work—sorting out domestic disputes, car accidents, and neighbors fussing at each other. They undoubtedly knew how to investigate petty theft, home burglaries, or teenage vandalism. That kind of nuts-and-bolts, small-time crime was on the menu every day for them.

Chris’s

case was different. It was difficult. No one had any reason to hurt her. She had no enemies or angry ex-husbands, no affairs gone south or riches someone wanted to plunder. I’d told police I believed it had to have been an intruder, someone who broke in after I left—someone who may even have chosen Chris at random. It was the only scenario that made sense.

Now, having watched these men work the crime scene and work me over had convinced me of one thing: they were never going to solve the case without help. Whoever killed Chris would never be caught, would be free to ruin another family’s lives, to destroy somebody else’s world as thoroughly as they had decimated mine.

It made me sick. I had been there answering the same questions for hours and I was frustrated, exhausted, and anxious about their inability to do their jobs.

I had to do something to move things forward.

When the sheriff hurled his next accusation at me, I blurted, “If I take a polygraph, then will you believe me?”

The two men lit up like kids on Christmas morning. That was exactly what they wanted to hear but never dreamed I would offer.

The sheriff told me he would schedule one for that evening at 6:00. I was to meet him back there at the Sheriff’s Department and we would be done in a flash. It seemed worth it to me. I wasn’t afraid of polygraphs—my employer had used them on occasion, for years. New hires and managers who handled a great deal of money or prescription drugs were regularly required to take them. I’d taken a test myself and was familiar with the science of how polygraphs worked.

I very much believed that since I had nothing to hide, I had nothing to fear. And I prayed that clearing me once and for all would lead the cops to look elsewhere before the killer’s trail got too cold.

I climbed back into my truck and headed home, hoping I might be able to catch a nap, or at least collapse in a quiet room with Eric—maybe play together with his cars and recharge our own batteries a little bit.

Getting Life

Getting Life